Efficient Shell Bash Writing

Fleeting- test if in a pipe

- use < /dev/tty for ALL interactive inputs

- beware pipes that will make the command pass

- beware of command substitutions that won’t make the program stop ’echo “$(false)”’

- Kill child jobs on script exit : A Weird Imagination

- values unpacking

- strings

- understanding file descriptor duplication

- use subshell with traps

- bash redirect output to the same file as taken as input by piping into a sponge

- bash manipulate substrings

- craft a custom bash completion out of another one, like an alias

- bkt to cache commands

- manipulate arrays in bash

- bash split string on delimiter, assign segments to array (like PATH and semicolon)

- slice an Array in Bash

- create arrays

- add values to array

- dereference array, without messing up with spaces

- append/concatenate arrays in bash, without messing up with spaces

- size of an array

- building args before calling a function

- Defensive programming with bash

- Notes linking here

- Permalink

efficient bash writing

test if in a pipe

test -t 1

use < /dev/tty for ALL interactive inputs

The following command comes naturally when processing several pieces of information and asking for user input in the process.

mycommand | while read line; do echo -n "$line" ; read -p "Is that line relevant to you" ; done

But, the inner read while also read the output of mycommand.

This can be even trickier when the code is split.

ask_for_user_input () {

read -p "Is that line relevant to you"

}

mycommand | while read line; do echo -n "$line" ; ask_for_user_input ; done

Instead, tell explicitly to your command that it should read from the user input.

ask_for_user_input () {

read -p "Is that line relevant to you" < /dev/tty

}

mycommand | while read line; do echo -n "$line" ; ask_for_user_input ; done

beware pipes that will make the command pass

false > /tmp/log.txt

exits with code 1

While

false | tee /tmp/logs.txt

Passes

Either explicitly ask bash to fail in that case

set -o pipefail

false | tee /tmp/logs.txt

Or deal with the PIPESTATUS

false | tee /tmp/logs.txt

exit "${PIPESTATUS[0]}"

beware of command substitutions that won’t make the program stop ’echo “$(false)”'

Whenever you use the pattern $() in a string, even with set -e and shopt -s inherit_errexit, bash will not stop.

set -e

shopt -s inherit_errexit

echo "Using a command that fails $(false)"

echo "This should not be printed"

Using a command that fails

This should not be printed

Instead, put those in temporary variables. This command fails like we want to.

set -e

shopt -s inherit_errexit

tempresult_="Using a command that fails $(false)"

echo "${tempresult_}"

echo "This should not be printed"

or

set -e

shopt -s inherit_errexit

tempresult_="$(false)"

echo "Using a command that fails ${tempresult_}"

echo "This should not be printed"

Kill child jobs on script exit : A Weird Imagination

- External reference: https://aweirdimagination.net/2020/06/28/kill-child-jobs-on-script-exit/

Kill child jobs on script exit : A Weird Imagination

At the start of the script, add cleanup() {

pkill -P $$}

for sig in INT QUIT HUP TERM; do trap " cleanup trap - $sig EXIT kill -s $sig “’"$$”’ “$sig” done trap cleanup EXIT

— https://aweirdimagination.net/2020/06/28/kill-child-jobs-on-script-exit/

example code to run a cleanup function on exit, even if exiting due to being killed by a signal that would normally halt the script immediately (obviously except for SIGKILL): for sig in INT QUIT HUP TERM ALRM USR1; do trap " cleanup trap - $sig EXIT kill -s $sig “’"$$”’ “$sig” done trap cleanup EXIT

— https://aweirdimagination.net/2020/06/28/kill-child-jobs-on-script-exit/

kills all immediate child processes of the script by killing all processes whose parent is the script: pkill -P $$

— https://aweirdimagination.net/2020/06/28/kill-child-jobs-on-script-exit/

Another option is killing all descendants using rkill: rkill $$

— https://aweirdimagination.net/2020/06/28/kill-child-jobs-on-script-exit/

another possible interpretation of killing all child jobs: it’s possible that what we want is to kill all jobs which have not been disowned. Unfortunately, this quickly runs into differences between shells.

— https://aweirdimagination.net/2020/06/28/kill-child-jobs-on-script-exit/

Another alternative that almost works is kill $(jobs -p)

It works in bash, but dash has a bug that requires the workaround of writing the output of jobs -p to a file and reading that file back. Then it works in every shell I tested except zsh where the jobs builtin does not have a -p option

— https://aweirdimagination.net/2020/06/28/kill-child-jobs-on-script-exit/

values unpacking

read var1 var2 var3 < <(echo "a b c")

echo "${var1}, ${var2}, ${var3}"

a, b, c

strings

get a substring

a="some string"

echo "${a:0:3}"

echo "${a:3:6}"

som

e stri

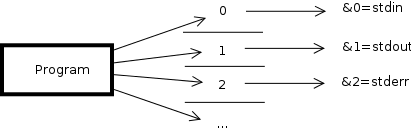

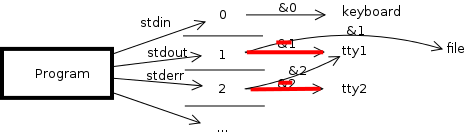

understanding file descriptor duplication

File descriptors and files

Programs don’t see files, they only see integers referring to files (remember a file may be a lot of things in linux). When a program opens a file for reading for instance, linux adds an entry into a file descriptor table that, well… describes the file. The program is then given the index in the table pointing to the file.

When a program is launched, three files descriptors are opened by default:

- the entry number 0 is generally called stdin and points to a read only file associated to the keyboard, bash refers to this file using &0

- the entry number 1 is generally called stdout and points to a write only file association to the current terminal, bash refers to this file using &1

- the entry number 2 is generally called stderr and points to a write only file association to the current terminal, bash refers to this file using &2

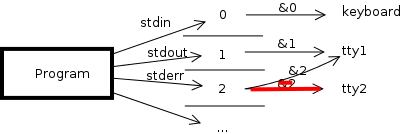

Stdout and stderr are not associated to the same file, but both file are by default associated to the current terminal. I will call them tty1 and tty2 but it is probably a misuse of the words tty. I don’t know how it works.

If I open a file, the file descriptor 3 will be used to communicate with this file and bash will allow to refer it as &3.

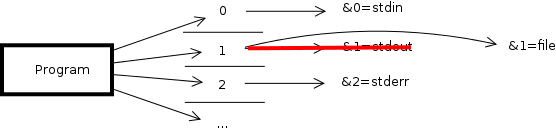

Interpretation of the bash commands

The commands file descriptor manipulation are executed from left to right. (note: > file is equivalent to 1> file)

command > file 2>&1

This means:

- redirect the content going to file descriptor 1 to the file. The old file is no more pointed to by file descriptor 1

- then, redirect the content going to the file descriptor 2 to the file pointed by the file descriptor 1

Then this commands concatenates the stdout and the stderr contents and put them into file.

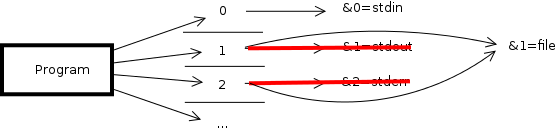

command 2>&1 > file

This means:

- redirect the content going to the file descriptor 2 to the file pointed by the file descriptor 1

- then, redirect the content going to file descriptor 1 to the file. The old file is no more pointed to by file descriptor 1

Therefore, this command writes the stderr on the file initially associated to stdout and writes stdout in the file.

Diagram

The source of the diagrams is here:

use subshell with traps

As a quick rule of thumb, try to always have the trap instruction be the first stuff after the start of the shell or a subshell.

In case you need some temporary stuff to be cleaned at the end of a function, a trap is quite useful. Remember though that some other part of the code might have put a trap to.

This is an example of a function that does not use a subshell.

f () {

TMP="$(mktemp -d)"

trap "echo cleaning ${TMP} ; rm -rf '${TMP}'" 0

echo "Doing something with temporary directory ${TMP}"

}

In the program, you might also put a trap.

trap "echo cleaning some main things" 0

f

Doing something with temporary directory /home/sam/tmp/tmp.dX4LQJFtDL

cleaning /home/sam/tmp/tmp.dX4LQJFtDL

Here, we can see that the main things were not cleaned.

Using a subshell in f. The difference is that we use ( instead of { in the

body of the function.

f () (

TMP="$(mktemp -d)"

trap "echo cleaning ${TMP} ; rm -rf '${TMP}'" 0

echo "Doing something with temporary directory ${TMP}"

)

Then, the main code results in

Doing something with temporary directory /home/sam/tmp/tmp.OJPDLaRTdH

cleaning /home/sam/tmp/tmp.OJPDLaRTdH

cleaning some main things

You can use subshell only for a piece of code in the function. For instance if you need the function to change a global state.

f () {

somevariable=1

(

TMP="$(mktemp -d)"

trap "echo cleaning ${TMP} ; rm -rf '${TMP}'" 0

echo "Doing something with temporary directory ${TMP}"

)

}

trap "echo cleaning some main things" 0

somevariable=0

echo "before being changed by f, somevariable=${somevariable}"

f

echo "after being changed by f, somevariable=${somevariable}"

before being changed by f, somevariable=0

Doing something with temporary directory /home/sam/tmp/tmp.0jpHirUWWk

cleaning /home/sam/tmp/tmp.0jpHirUWWk

after being changed by f, somevariable=1

cleaning some main things

Traps also work when nested.

(

trap "echo outer" 0

(

trap "echo inner" 0

)

)

inner

outer

Also, beware that exec will substitute the bash process with the run one, then the trap won’t be run.

trap "echo end" 0

echo ok

ok

end

trap "echo end" 0

exec bash -c "echo ok"

ok

bash redirect output to the same file as taken as input by piping into a sponge

bash redirect output to the same file as taken as input

Bash will start opening the output file, making it empty for reading.

TMP="$(mktemp -d)"

trap "rm -rf '${TMP}'" 0

cd "${TMP}"

echo something > f

echo something else >> f

cat f

something

something else

cat f | grep else > f

Then, showing again, the file is empty

While using sponge

cat f | grep else | sponge f

Now, the file contains only the else line, as expected.

something else

bash manipulate substrings

bash remove suffix/prefix

take substring

a=foo/bar/baz.txt

echo "${a:3}"

/bar/baz.txt

a=foo/bar/baz.txt

echo "${a::3}"

foo

a=foo/bar/baz.txt

echo "${a:3:7}"

/bar/ba

remove suffix (like an extension)

a=foo/bar/baz.txt

echo "${a%*.txt}"

foo/bar/baz

This also works with partial content

a=foo/bar/baz.txt

echo "${a%*/bar*}"

foo

remove prefix

a=foo/bar/baz.txt

echo "${a#foo/*}"

bar/baz.txt

This also works with partial content

a=foo/bar/baz.txt

echo "${a#*bar/*}"

baz.txt

keep prefix

a=foo/bar/baz

echo "${a%/*}"

foo/bar

a=foo/bar/baz

echo "${a%%/*}"

foo

keep suffix

a=foo/bar/baz

echo "${a#*/}"

bar/baz

a=foo/bar/baz

echo "${a##*/}"

baz

craft a custom bash completion out of another one, like an alias

craft a custom bash completion out of another one

Say I want to

#!/bin/bash

ME="$(basename "${BASH_SOURCE[0]}")"

source /usr/share/bash-completion/completions/apt

_sai () {

# take the words without the initial sai and substitute it with "sudo apt install"

COMP_WORDS=(sudo apt install "${COMP_WORDS[@]:1}")

# then, add 2 to cword because I added two words (actually removed 1 and

# added 3, but who cares?)

COMP_CWORD=$((COMP_CWORD + 2))

# then, update the line and the point,

COMP_LINE=${COMP_LINE/sai/sudo apt install}

COMP_POINT=$((COMP_POINT + 13)) # sudo apt install contains 13 characters more than sai

_apt

}

complete -F _sai "${ME}"

bkt to cache commands

caching bash commands

manipulate arrays in bash

bash split string on delimiter, assign segments to array (like PATH and semicolon)

-

External reference: https://stackoverflow.com/questions/15777996/bash-split-string-on-delimiter-assign-segments-to-array

IFS=: read -a arr <<< “$foo”

— https://stackoverflow.com/questions/15777996/bash-split-string-on-delimiter-assign-segments-to-array

slice an Array in Bash

-

External reference: https://www.tutorialkart.com/bash-shell-scripting/bash-array-slice/ bash

${arrayname[@]:start:end}

— https://www.tutorialkart.com/bash-shell-scripting/bash-array-slice/

create arrays

emptyarray=()

somearray=(value1 value2)

add values to array

somearray+=("value3 with space" value4)

dereference array, without messing up with spaces

for value in "${somearray[@]}"

do

echo ${value}

done

value1

value2

value3 with space

value4

See how the “value with space” is correctly dealt with?

append/concatenate arrays in bash, without messing up with spaces

someotherarray=("some other value" "some more")

somearray+=("${someotherarray[@]}")

for value in "${somearray[@]}"

do

echo ${value}

done

value1

value2

value3 with space

value4

some other value

some more

somenewarray=("${someotherarray[@]:1}" "${somearray[@]:0:3}")

for value in "${somenewarray[@]}"

do

echo ${value}

done

some more

value1

value2

value3 with space

size of an array

a=(a b c)

echo "${#a[@]}"

a=()

echo "${#a[@]}"

3

0

building args before calling a function

args=(-c "print('something')")

args+=(-s -v)

args+=(-b)

python3 "${args[@]}"

something

Defensive programming with bash

Defensive programming with bash

According to https://vaneyckt.io/posts/safer_bash_scripts_with_set_euxo_pipefail/, use src_sh[:exports code]{set -Eeuo pipefail}

- set -e

- The -e option will cause a bash script to exit immediately when a command fails.

- set -o pipefail

- Sets the exit code of a pipeline to that of the rightmost command to exit with a non-zero status, or to zero if all commands of the pipeline exit successfully.

- set -u

- This option causes the bash shell to treat unset variables as an error and exit immediately.

- set -E

- using -e without -E will cause an ERR trap to not fire in certain scenarios

— https://vaneyckt.io/posts/safer_bash_scripts_with_set_euxo_pipefail/

The author also recommends to use -x, but I think it is way too verbose to be

useful in the general use case.

According to https://dougrichardson.us/2018/08/03/fail-fast-bash-scripting.html, use

set -euo pipefail

shopt -s inherit_errexit

I like being explicit, and I like my code to fail fast, thus I suggest:

set -o errexit # -e

set -o errtrace # -E

set -o nounset # -u

set -o pipefail

shopt -s inherit_errexit

Fail Fast Bash Scripting

-

External reference: https://dougrichardson.us/2018/08/03/fail-fast-bash-scripting.html Fail Fast Bash Scripting

Summary Put this at the top of your fail-fast Bash scripts:

#!/bin/bash set -euo pipefail shopt -s inherit_errexit